Anyone familiar with Allied clandestine operations during World War II (e.g., British-led Special Operations Executive – SOE, Gen. de Gaulle’s Bureau Central de Renseignements et d’Action – BCRA, and America’s Office of Strategic Services – OSS) is aware of two things: first, women were used as undercover agents operating behind enemy lines and many of them were very successful. (Alas, too many female agents were executed by the Germans or killed in the line of duty.) Second, after the war, these women were either abandoned by their agencies or forced to work in pre-war job assignments (e.g., secretarial). Many of the former female field agents’ male bosses felt threatened, especially when the man had no field experience. Those attitudes held back many talented women who believed (and rightfully so) they had not only proved themselves but could contribute even more to a post-war world.

It was a “man’s world” back in those days and this was especially true in the world of espionage. Six years after the formation of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), a group of women had a meeting with the agency’s new director, Allen Dulles (1893−1969), for the purpose of determining his attitude toward roles of women working for the CIA. During the meeting, they asked the director three pointed questions. (Soon after, a senior CIA manager called these women, the “Wise Gals.”) The outcome of this meeting was the formation of a thirteen-member panel to study the issues raised earlier. This group of women became known as the “Petticoat Panel.”

Click here to see our most recent book.

Did You Know?

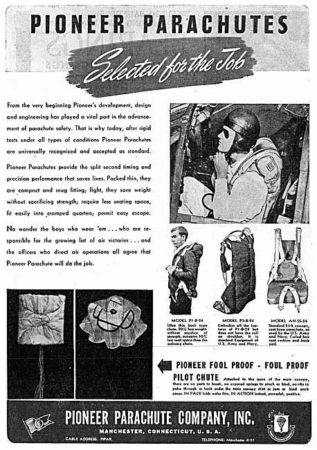

Did you know that Cheney Silk Mills in Manchester, CT (USA) established the Pioneer Parachute Company in 1938? Pioneer supplied almost all the silk parachutes to the United States government during World War II. One of Manchester’s residents, Pfc. Robert C. Hillman (1924 – 1993), was a member of the “Screaming Eagles” of the 101st Airborne Division. He was one of thousands of “Pathfinders” who jumped into the dark of northern France six hours before the D-Day invasion ships began shelling Normandy and releasing landing craft onto the beaches. A jumper had to have complete confidence in his parachute for obvious reasons.

As the men sat in their aircraft waiting for the jump signal, most were, understandably, very nervous. Not Hillman. He was supremely confident that his parachute was packed correctly, and it would perform its function without a flaw. Pfc. Hillman recognized the parachute as having been manufactured and packed in his hometown. However, there was an even more important reason why Hillman never gave it a second thought.

Every parachute carried the initials of the person who packed and inspected it. When he received his parachute, he first looked at the packing tag. Hillman recognized the initials of the person who inspected the chute. That person was his mother. She worked at Pioneer Parachute and at that moment, Hillman knew his parachute would open as expected.

Pfc. Hillman successfully jumped into France that night and survived the war. After the war, he returned to Manchester and worked for Cheney before being called back to duty to serve in the Korean conflict.

The Office of Strategic Services

Intelligence gathering for the United States government was historically decentralized among various military and political branches. President Franklin D. Roosevelt became so concerned about possible intelligence deficiencies that he ordered William Donovan (1883−1959) to draft a plan for consolidating intelligence and special operations into one agency. This new organization, “Coordinator of Information” (COI) was based on two British spy agencies: MI6 and the SOE. By June 1942, the COI morphed into the Office of Strategic Services with “Wild Bill” Donovan as its wartime leader. (Donovan was a World War I veteran and Medal of Honor recipient.)

The mission of the OSS was to collect and analyze strategic information for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It was also assigned the responsibility to execute special operations. In reality, intelligence gathering remained a decentralized function spread out among the FBI (primarily domestic) and the separate military branches. (By comparison, the Nazis also had duplicate spy agencies: the Abwehr and the Sicherheitdienst, or SD.)

One of Donovan’s strengths was his ability to recognize and promote intelligent and talented individuals. Wild Bill didn’t care about a person’s gender or skin color. If he thought someone had talent and could perform well in the field, they were hired. Donovan’s views were likely influenced by the success of SOE female agents in France. Two of Donovan’s best field agents during the war were Virginia Hall (1906−1982) and the future CIA director, Allan Dulles, head of Switzerland operations. Other OSS agents included Julia Childs (television food celebrity), Sterling Hayden (actor), Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. (historian), and John Ford (film director).

President Harry Truman, successor to Roosevelt, did not fancy to secretive government agencies and he dissolved the OSS months after the end of World War II. The agency’s functions were divided between the departments of state and war. Despite strong opposition from the state department, the FBI, and the military, Truman finally came around to the idea of a centralized information gathering agency. In January 1946, the Central Intelligence Group (CIG) was created. By 1947, the CIG and other intelligence agencies were dissolved, and the CIA was created.

The Central Intelligence Agency

One of the major reasons President Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947 (establishing the CIA) was the growing tension between the United States and the Soviet Union (i.e., Cold War). The original and core mission of the CIA was to gather and centralize intelligence information “to inform the U.S. president about events, developments, and threats that he and his policymakers might not otherwise be able to perceive.” However, there were certainly growing pains in the early years of the agency as evidenced by Truman’s total surprise (as well as the National Security Council) when North Korea invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950. The invasion and other intelligence failures (e.g., Soviet takeover of Romania, the Berlin blockade, and the Soviet’s nuclear bomb project) exposed the weakness in the agency’s ability to gather intelligence. Shortly after the invasion of South Korea, Truman appointed Walter Bedell Smith (1895−1961) as the agency’s first director. (Gen. Smith served as Gen. Eisenhower’s chief of staff during World War II.)

After Eisenhower was elected president in 1952, Smith left the CIA for the state department and Allen Dulles was appointed as the first civilian director of the spy agency. Dulles was responsible for the agency’s “New Look,” or the expansion of its overseas covert operations. (The original CIA charter banned the agency from domestic spying.) He convinced Eisenhower to publicize the Soviet nuclear threat and to confront Sen. Joseph McCarthy (1908−1957) regarding the senator’s accusations of communist infiltration in the CIA.

Shortly after his appointment, Dulles promised to “devote the balance of [his] time [at the CIA] to build up the agency’s espirit de corps, its morale, its effectiveness, and its place in the government of the United States.” On 8 May 1953, Dulles addressed CIA officers at the 10th Agency Orientation Course. After his comments, Dulles opened the meeting for questions. A group of women wanted to know the new director’s thoughts on the role of women in the CIA. They were “The Wise Gals.”

The Wise Gals

The group of women pressed Dulles for answers to three questions. First, why are women hired at a lower grade than men? Second, did Dulles believe women were given significant recognition within the CIA? And third, was Dulles going to do anything to counter the professional discrimination against the women in the agency?

Shortly after the “Wise Gals” confronted Dulles with their questions, the director authorized the inspector general (IG), Lyman Kirkpatrick (1916−1995), to investigate and produce a report outlining the agency’s discrimination against women. Dulles said, “I think women have a very high place in this work. And if there is discrimination, we’re going to see that it’s stopped.” Based on the results of the IG, Dulles convened a panel of women to analyze the various issues concerning discrimination. However, the panel went one-step further.

The Petticoat Panel

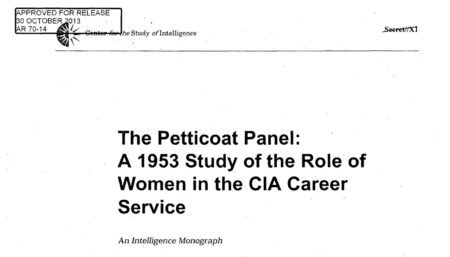

The Petticoat Panel refers to the CIA’s first attempt to study the role of women in the world of intelligence (and counterintelligence). The thirteen members of the panel (nine alternates) saw their mission as two-fold: first, determine whether there was discrimination against women in the spy agency. Second (and probably not what Dulles intended), to make recommendations on solving the problems of discrimination and career development.

Each of the panel members had to be a career CIA employee with roots in either the OSS or the early days of the CIA and a member must be able to speak with authority about the business of intelligence. In fact, many of the members had field experience ⏤ something many of their male bosses never had.

On 31 July 1953, the first meeting of the panel took place. Dorothy Knoelk was elected as the panel’s chair while Bertha Bond became its secretary. The panel produced a comprehensive and well-researched report that was presented to the Career Services Board (CSB). The report found the agency “has not taken full advantage of the womanpower resources available to it.” Statistically, the report pointed out that only 19% of agency women were in grades higher than GS-7 compared to 69% of men. Only 7% of women held field operative positions while 25% served as officers in CIA headquarters. (Forty percent of the agency’s total workforce were women at the time.)

Petticoat Panel Members

I’d like to introduce you to several female CIA agents as well as some of the Petticoat Panel members.

Eloise Page (1920−2002) worked under ‘Wild Bill” Donovan as his secretary at the OSS and then transitioned over to the CIA in 1947 when the agency was created. After progressing through her career in espionage and intelligence, Eloise became the agency’s first station chief in 1978 when she was assigned to Athens, Greece. Subsequent assignments included promotion to Deputy Director of the Intelligence Community staff and chairing the Critical Collection Problems Committee. At the end of her career, Eloise became an internationally known expert on terrorism and upon her retirement in 1987, Eloise consulted on terrorism at the Defense Intelligence Agency. Eloise lived long enough to be honored by the CIA with its “Trailblazer” award. Between 1975 and her retirement, Eloise (aka “The Iron Butterfly”) was the CIA’s highest ranking female officer. One CIA colleague said of Eloise, “She was a perfect southern lady with a core of steel.”

Virginia Hall (1906−1982), one of the greatest World War II field spies for the SOE and OSS, was hired by the CIA in 1947 as its first woman employee. Virginia was the only civilian woman to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for her efforts during the war and she was honored by the British with an MBE and the French Croix de Guerre. Assigned to a desk job, Hall was purposely given inferior performance evaluations, denied promotions, and honors for her superior work. She resigned in 1948 but returned in 1950 to another desk job. I recommend you visit the “Recommended Reading” section at the end of this blog where I have given you the names of two biographies on Virginia Hall, the “limping lady.”

Jane Wallis Burrell (1911−1948) was the first CIA officer to die while employed by the agency (110 days after the CIA was formed). Like Eloise Page, Jane Burrell served in the OSS under Donovan and made the successful transition to the CIA. At a time when most women were typists and clerks within the CIA, Jane came into the agency as a CIA counterintelligence officer. In this capacity, Jane worked primarily on German cases. (Presumably using intelligence gathering to capture Nazi war criminals as well as supporting the “denazification” process.) While returning to Belgium from a CIA operational mission, Jane’s plane went down, and she did not survive. The official CIA statement was that Jane Burrell was on holiday at the time of the crash. (Click here to read the blog, Killed in the Service of Her Country.)

Mary Hutchison was a panel member who had served between 1942 and 1946 in the Navy WAVES or, “Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services”). She was bilingual in five languages and received her doctorate from the University of Missouri. When Richard Helms (1913−2002) offered Dr. Hutchison a position as his secretary, she declined. Mary told Helms the position would be a waste of her talents. Helms agreed and Mary become one of CIAs first female reports officer. Mary fought for equal salary levels between male and female agents. Prior to retiring in 1970, Mary’s last performance report tried to explain the lack of recognition; “Subject is one of the unfortunately passing breed who are in CIA because they believe in what it is doing rather than for what it is paying them.”

Adelaide Hawkins also sat on the panel. She joined the Army Signal Corps and became a respected cryptologist. In December 1941, Adelaide was in charge of the message center in Washington, D.C. where she specialized in secret codes, or ciphers. At the same time, Adelaide trained spies to operate behind enemy lines. She joined the CIA after the war and became its chief of covert communications. In 1956 while stationed in the U.K., Adelaide was responsible for uncovering violations of Israel’s negotiated allowance of fighter planes. Around the same time, she and her team discovered that America’s allies, France, Britain, and Israel, were secretly plotting to seize the Suez Canal. She was not considered for promotion to branch chief because the position was, “. . . being held open for a man with the mathematical background.”

Margaret McKenny joined the U.S. Civil Service in 1940 and went to work in the War Department where she stayed until 1946. That year, Margaret moved over to the CIA where she was assigned to the personnel department until her retirement in 1976. (Margaret was an alternate on the Petticoat Panel.) During her career, Margaret was the first director of the agency’s “Federal Women’s Program Coordinator.” She became the chair of the CIA’s Women’s Advisory Panel in the early 1970s and was responsible for drafting the agency’s 1974 EEO Affirmative Action Plan.

Dorothy Knoelk chaired the Petticoat Panel. Her entire career with the CIA was spent as a training officer. She had her bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan and a masters from Columbia University. In 1952, she was promoted to Chief of the Clerical Training Branch where her supervisor wrote, “. . . Miss Knoelk is qualified to handle any position, where women are acceptable, . . .” By 1956, her performance was again rated with the comment, “She has met and overcome the subtle handicap of being a woman . . .”

Elizabeth Sudmeier (1912−1989) was not a panel member or alternate. However, she is recognized as having contributed to the panel’s report. Elizabeth joined the “Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps” at the outset of World War II. The CIA has officially acknowledged Elizabeth as one of the agency’s charter members in 1947. During the 1950s, Ms. Sudmeier was a counterintelligence field operative with responsibility for gathering intelligence. She spent nine years assessing Soviet military hardware. She was awarded the “Intelligence Medal of Merit” in 1962 but it did not come without controversy. Elizabeth’s male counterparts objected because they did not feel it was appropriate for a woman to be honored with the medal. After her passing, Elizabeth was nominated as a CIA “Trailblazer.”

| Sitting Panel Members: | Bertha Bond | (1921−1975) |

| Evangel Cowly | (1917−1975) | |

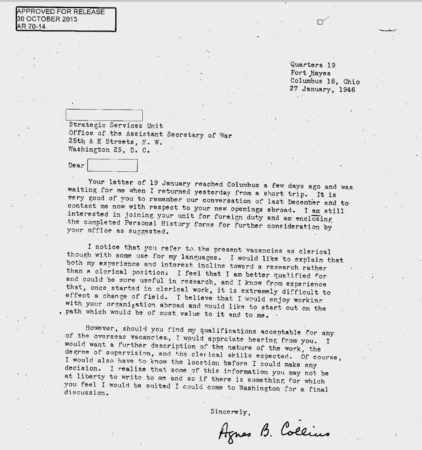

| Agnes Collins | (1920−?) | |

| Louise Davison | (1915−?) | |

| Charlotte Gilbert | (1893−?) | |

| Evelyn Hall | (1912−?) | |

| Helen Hanson | (1913−1995) | |

| Adelaide Hawkins | (1914−2008) | |

| Mary E. Hutchison | (1911−2007) | |

| Dorothy Knoelk | (1909−1962) | |

| Dorothy McMillan | (1905−?) | |

| Sylvia Warner | (1911−2015) | |

| Jeanne Lettellier | (1911−?) | |

| Alternates | Marion Shaw | (1920−?) |

| Beth Enid Marks | (1915−?) | |

| Margaret Slusser | (1911−?) | |

| Emily Jack | (1916−?) | |

| Ruth Robinson | (1912−?) | |

| Margaret McKenny | (1916−?) | |

| Deborah Verry | (1910−1965) |

Panel Results

The panel’s report uncovered discriminatory attitudes toward CIA women. It found a “traditional attitude toward women” that could only be corrected over time through social change. Attitudes of the men included, “women are more emotional and less objective in their approach to problems.” Discriminatory evidence also included the attitudes that, “women can’t work under the pressures of urgency.” Another finding concluded there were very narrow opportunities for career advancement for women. The careers in the CIA for women were only in low-level positions. (I suspect none of this came as a surprise to the women of the CIA.)

Unfortunately, the Panel’s recommendations were rejected. On 28 January 1954, the official response to the report was, “The status of women in the agency does not call for urgent corrective action, but rather for considered and deliberate improvement primarily through the education of supervisors.”

The CSB did acknowledge, “Women should be considered on the same basis as men for any and all vacancies.” Unfortunately, neither the CSB or the agency followed through on the implementation of the panel’s recommendations. However, the good news is that the Petticoat Panel’s suggestions provided the catalyst for future generations of CIA women.

“It is just nonsense for these gals to come in here and think the government is going to fall apart because their brains aren’t going to be used to the maximum.”

⏤ Richard Helms

DDP, Chief of Operations

Future Director of Central Intelligence

(c. 1970s)

The Persistent Glass Ceiling

On 21 May 2018, Gina Haspel (b. 1956) was sworn in as the first female director of the CIA. (She retired in 2021 after a thirty-six-year career in the CIA.) Unfortunately, between the time of the Petticoat Panel and Haspel’s appointment, the culture of men within the agency got worse. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the agency grappled once again with the same issues from 1953. (The CIA created the “Women’s Advisory Panel” for the purpose of advocating promotions, training, and reassignments.) Women began to complain about working harder than their male counterparts to get a promotion, they could not get promotions to case offices, salary inequalities, and hiring based on merit. Harritte Thompson (?−2013), a career intelligence officer, filed a lawsuit in 1977 covering these issues. She ultimately settled with the CIA, and with it, you’d think the agency would shatter the gender “Glass Ceiling.” But it didn’t.

By 1983, forty percent of the CIA workforce was women, but they were concentrated in the lower grade categories. The glass ceiling still existed. The deputy director, John McMahon wrote a memo that year entitled, “CIA Women.” It was a comprehensive study on gender employment at the CIA. Mr. McMahon went on record as saying, “I am embarrassed.” Nine years later, the CIA created yet another report called the “Glass Ceiling Study” to determine what career barriers existed for agency women and minorities. You have to wonder how many reports or studies were prepared over the years only to have recommendations stymied at the senior administrative level.

The CIA Museum

The Central Intelligence Agency established its own museum honoring certain agents (e.g., Virginia Hall), displaying historical artifacts (e.g., the gun that killed Osama bin Laden, the scale model of bin Laden’s compound, and Saddam Hussein’s leather jacket), and highlighting historical missions (e.g., Bay of Pigs and the late 1960s attempt to recover the wreck of a sunken Soviet submarine). The museum also presents a chronological history of the CIA from its formation in 1947 through the Cold War years, and its efforts at counterterrorism.

There is a CIA memorial wall dedicated to agents who died while in the line of duty. There are 137 engraved stars and names on the wall. Forty-five died accidently with the majority perishing in plane crashes. Jane Burrell does not have her name or star on the wall. She was returning to Brussels when her plane went down after a secret mission to talk to war crimes investigators. If any of you have the time, please write your senator or congressperson, and request a star for Jane on the memorial wall.

The problem with the museum, as you can imagine, is that it is top secret. Well, sort of. It is located within the CIA headquarters at Langley, Virginia and as such, the museum is not open to the public. If you want to experience its multiple exhibits, they ask you to visit virtually.

Click here to visit the museum.

There are five exhibits dedicated to individual CIA operatives. One is Virginia Hall and the other four are men who eventually went on to become the agency’s director. The CIA eventually acknowledged Hall’s contributions (including organizing resistance networks behind the Iron Curtain) and in 2016, named its field agent training facility as the “Virginia Hall Expeditionary Center.”

Next Blog: “The Ten Gifts of the White Bus Rescues”

A Guest blog by Dr. Roger Ritvo, Caitlyn Traffanstedt, and Allison Stone

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Bourne-Paterson, Major Robert. SOE in France 19411945: An Official Account of the Special Operations Executive’s “British” Circuits in France. Barnsley, U.K.: Frontline Books, 2016.

Holt, Nathalia. Wise Gals: The Spies Who Built the CIA and Changed the Future of Espionage. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2022.

Jeffreys-Jones, Rhodri. A Question of Standing: The History of the CIA. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2022.

Pearson, Judith L. The Wolves at the Door: The True Story of America’s Greatest Female Spy. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2005.

Purnell, Sonia. A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II. New York: Viking, 2019.

Reynolds, Nicholas. Need to Know: World War II and the Rise of American Intelligence. New York: Mariner Books, 2022.

Rossiter, Margaret L. Women in the Resistance. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1986.

Smith, Richard Harris. OSS: The Secret History of America’s First Central Intelligence Agency. Lanham, MD: Lyons Press, 2005.

Talbot, David. The Devil’s Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America’s Secret Government. New York: Harper Perennial, 2016.

Waller, Douglas. Disciples: The World War II Missions of the CIA Directors Who Fought for Wild Bill Donovan. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

(Redacted last name of the author), Jacqueline. The Petticoat Panel: A 1953 Study of the Role of Women in the CIA Career Service. An Intelligence Monograph. Central Intelligence Agency, 2003. Declassified 2013. Click here to read the article.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Welcome to the New Year, 2023. I hope this year will be the best one ever for each of you.

At the beginning of November, Sandy and I returned from our transatlantic cruise. Starting in Rotterdam, Netherlands where we boarded the ms Rotterdam (the seventh ship named for the city), we stopped at Le Havre and then Plymouth, England. From there, we headed across the North Atlantic to New York City for an overnight layover. After visiting the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, it was another two-days on the sea before reaching Fort Lauderdale in Florida and a short ride home.

We took this trip for two reasons. I wanted the experience of sailing out of Rotterdam at least once where we could spend a night at the Hotel New York. The iconic hotel was the former headquarters of Holland America and is situated at the end of the Wilhelmina Pier where the Rotterdam was docked. Second, I wanted to stand on the bow of a ship as it entered New York City’s harbor early in the morning. Passing by the Statue of Liberty gives one the feeling how those early century immigrants felt approaching their new country.

While on board, we met Joska, a guide dog for the blind. Her “mom and dad” were Cornelia and Cornelis. We always saw Joska while sitting in the Crow’s Nest where she would visit with all the passengers until Cornelis would call her. Their story is told in the following USA Today article. Click here to read the article.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank our friends, Fred S. and Kim F. for contacting us on several of the past blogs. Fred grew up in Camp King and is connecting with some of the folks we’ve been in touch with (click here to read the blog, Camp King). Kim F., as always, catches some of my French language mistakes. Our blog, Le Bleus, Le Collabo et L’exécution, originally was Le Bleus, Le Collabo et Le Exécution (click here to read the blog). Kim pointed out that you can’t use “Le” and have an “e” follow. It must be “L’exécution.” Thanks again to both of you for reaching out to us.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books (in our case, it is Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters?). The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross

Stew, I have written you before to say this, but I write again: I love your work!

I will be 87 in a few days and my interest in history, almost any history, increases as my ability to play golf decreases. My wife of 57 years, who is 86, was a little girl in a small village in Lorraine when the Germans rolled through. She was not much older when Patton and his tanks came the other way. It is interesting that my parents emigrated to the US in the 1920’s and that I had several relatives in the German armed forces. I went to the German cemetery in Normandy and found a grave with my exact name on it. This summer, during what I suspect may be our last visit to Europe, I plan to visit the graves of my paternal grandparents, which are in Poland (formerly Pomerania).

Thank you so much for what you do.

Hi Carl. Good to hear from you again. I very much appreciate your kind comment. Sorry to hear this will likely be your last visit to Europe. I hope it is a wonderful trip and you see things that are meaningful to your life. After you return, please let me know how the trip went. Stay in touch. STEW

As always, this generally unknown history of women’s participation the OSS and CIA was topnotch. I consider myself a better informed person as a result. Thanks, Stew.

Hi Greg, always great to hear from you. Thank you for your comment on the blog. It’s a seldom told story. One of the reasons why I picked this topic. STEW

I am a student researching this topic and this was very helpful.

Thank you Janae for contacting us. Good luck with your research and final product. STEW